Open Pit Programming: Silicon Valley’s Industrial Extraction of Human Potential Part II

Facebook’s motto, ‘move fast and break things,’ could have been written for hydraulic mining companies. Both unleashed unprecedented forces to extract maximum value, ignored downstream consequences and transformed their industries through sheer destructive efficiency. The difference? Hydraulic mining destroyed hillsides; social media plunders people’s humanity.

As a child I loved field trips to Malakoff Diggins State Park, a wild canyon-shaped scar in the foothill scrub just outside Nevada City in North Bloomfield. You can hike along the base of steep cliffs exposing white-grained clay up through peach to coppery iron-stained siltstone where the top of the escarpment meets pine forest, like the stratified ombre of a Thai iced tea. The pit, a little over a mile long and about half that wide was caused by 30 years of hydraulic mining.

In 1852, prospectors Edward Mattison and Anthony Chabot figured out how to use a water cannon to fast-track erosion of hillsides down into giant sluices. Why wait for gold to end up in creeks when you can make years of subsidence happen in minutes?

Hydraulic miners used quicksilver to bind gold during sluicing, flushing mercury-laced tailings downriver to poison waterways to the San Francisco Bay. Even without the heavy metals, the sediment alone wreaked havoc and caused flooding throughout the Sacramento Delta, causing significant loss of life and property. But the money was too good to stop the water cannons.

Mark Zuckerberg founded Facebook in the shadow of the dotcom bust, slithering into Silicon Valley in 2004. From 2006, the company saw hockey stick growth, where facebook.com saw more visits than google.com in 2010. The dawn of surveillance capitalism changed the topography of the web as effectively as water cannons decimated California hillsides. It was all about harvesting data from millions and millions of people, no matter the cost or level of toxicity downstream.

In the 1860s and 70s, citizens vocally protested the environmental dangers of hydraulic mining. Mining companies operated with virtually no regulations to restrict this devastating practice until activists filed a petition challenging the legislature.

Coincidentally, around that same time, the world’s first long-distance telephone line was strung across the foothills of California in 1877. It ran from French Corral to French Lake via Malakoff Diggins. My dad said they ran the telephone line to tip off mine operators when inspectors were on their way to monitor the volume of sluicing. The miners could turn off the hoses and get the Yuba River running clear of silt before the officials could show up and catch them transgressing the allowed limits.

It is only today that regulators are looking at seriously legislating social media. In January of 2024, Mark Zuckerberg testified before the Senate about social media. When asked if he would apologize directly to parents of suicide victims, he said, “I’m sorry for everything you’ve all gone through,” as if that could even begin to make up for their loss. He is right that “It’s terrible. No one should have to go through the things that your families have suffered.” But that is the epitome of too little, too late.

Tech companies aren’t all cartoon villains twirling their mustaches while they deplete their workforce, though the jury is out for Zuckerberg amidst the “low performance” layoffs and canceled moderation of 2025. Modern mining companies offer good salaries, benefits, and working conditions that would have been unimaginable to my mining ancestors. Innovation can still happen; some products delight users, and many workers find genuine fulfillment in their roles. However, good intentions and positive outcomes don’t negate the underlying pattern of treating human creativity as an extractable resource in service of enshittification. Like those early hydraulic mining companies, tech firms can provide good jobs while still participating in unsustainable practices. The question isn’t whether tech companies are ‘good’ or ‘bad’—it’s whether their current practices are ethical for their workers and society.

Speculation & Pyrite Promises

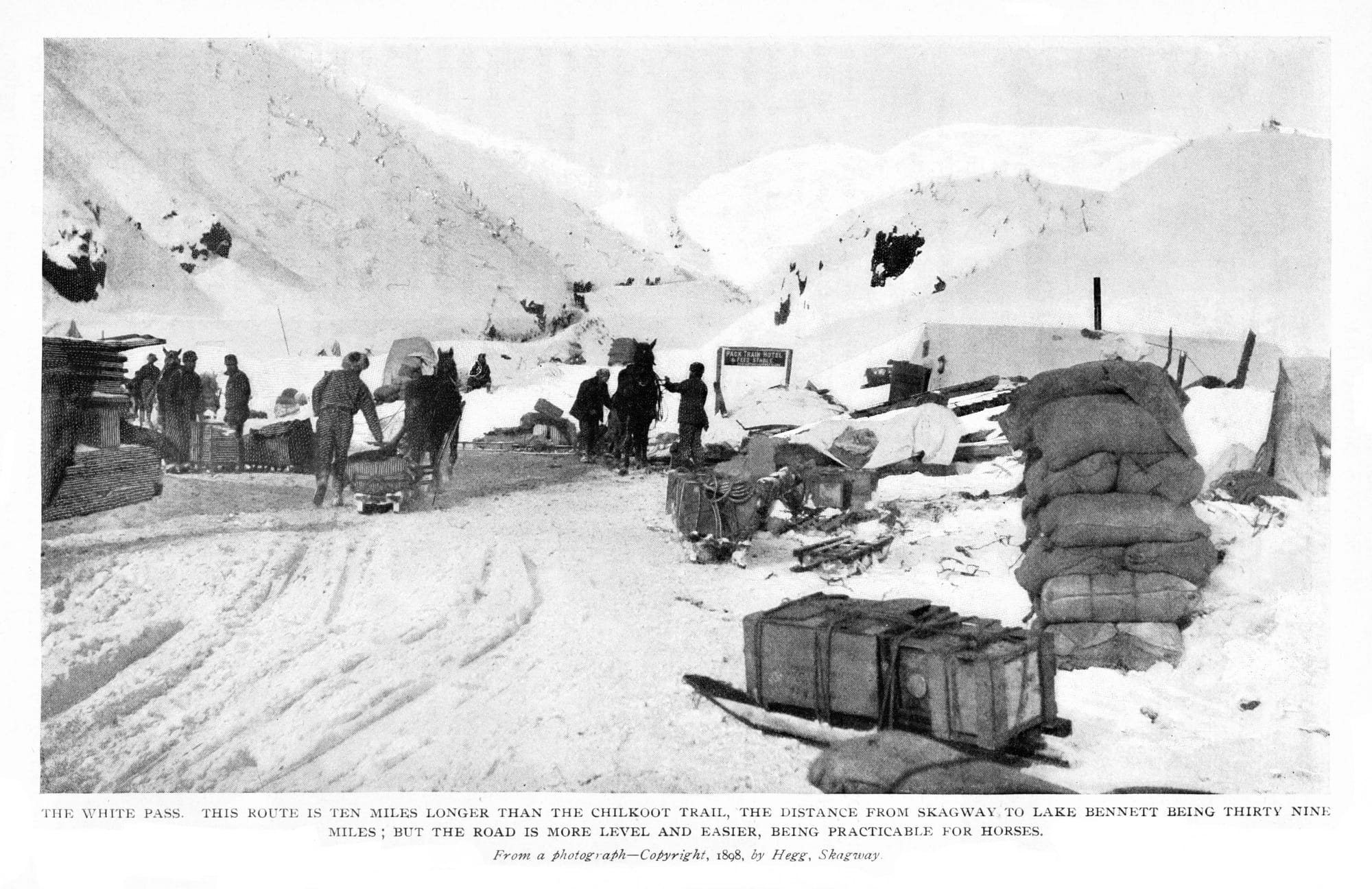

As tech’s fortunes rise and fall, so has the hunt for gold with waves of boom and bust. The Yukon Gold Rush of 1889 put Seattle on the map. As the last US stop for prospectors setting off to Alaska, the Emerald City stayed true to its pragmatic roots and sold everyone the requisite prospecting supplies. They had learned Samuel Brannan’s lesson from San Francisco’s resource stampede: “If you want to get rich, sell shovels.” There was no further west to go for the last adherents of manifest destiny, so why not go north?

The hundreds of thousands of people who made it up to Alaska found themselves in an icy wasteland, milling around with all the other disappointed adventurers. That speculation frenzy ended almost as fast as it started, but the news tickled slowly back down to the lower 48 (well 45 at that time).

Web3 was a solution looking for a problem, but everyone got excited because it felt like the early bonanza-style murmurings of the Dotcom boom. Just buy that URL and strike it rich! So much of the digital frontier had been plundered, and people were ready to be duped by rumors of easy pickings and the next big thing.

Crypto and blockchain delivered the same disenchantment as the Yukon strike. Web3 existed, the way gold was found in Alaska, but the promised fortunes are nowhere to be found. Like Humphrey Bogarts character Fred C. Dobbs in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, crypto bros watched their fortunes drive them to paranoia before dissolving into dust. The digital prospectors are a lot quieter these days, would rather not talk about their stale Xeets bragging about their luck.

Silicon Valley has traditionally seen IPOs as the most prestigious exit for venture-backed companies, though mergers and acquisitions have historically been more common. While going public represented the ultimate success story in the 1990s through 2010s, in recent years companies have increasingly relied on other exit strategies—from strategic acquisitions to private equity buyouts. But that money all comes with strings, from VC-stacked boards calling the shots about scaling to founders finding themselves beholden to Wall Street. The defiant kids who wanted to do something different from the traditional careers of their parents have circled back to find themselves the adults now, indebted to banks and mortgage lenders.

The pandemic’s global scope didn't change software tech itself; the industry was already distributed and often supported remote work, but it did change the funding landscape around it. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act fundamentally changed how tech companies could handle research and development costs under Section 174, though the change didn’t take effect until 2022.

Previously, companies could deduct all their R&D expenses immediately, including software development and engineering salaries. When this provision finally went into effect at the end of 2022, companies were forced to spread these deductions over five years for domestic R&D and fifteen years for foreign R&D. This seemingly arcane tax change hit tech particularly hard because software development had always been classified as R&D. Suddenly, companies needed more cash on hand to cover the same development costs.

The timing couldn’t have been worse: inflation was eating into cash reserves, and interest rates were climbing. Many companies responded by cutting their most expensive line item: headcount. The layoffs weren’t just about reducing staff but fundamentally restructuring how companies approached development. Projects that might have been given time to mature were now evaluated for immediate return. Like mining companies facing new regulations, tech firms optimized for quick extraction over long-term sustainability.

AI’s Atomic Moment

Watching my husband replay Fallout 4, its post-apocalyptic wasteland speaks to my current anxieties about technology run amok. The game’s soundtrack keeps lodging “Uranium Fever” in my head, a song I initially thought was created for this digital dystopia. But Elton Britt's 1955 country hit captured a unique moment in American history during the 1950s uranium prospecting boom when the Cold War drove high demand for nuclear materials.

Well, I don’t know, but I’ve been told / Uranium ore’s worth more than gold

Sold my Cad’, I bought me a Jeep / I’ve got that bug and I can’t sleep

Uranium fever has done and got me down / Uranium fever is spreadin’ all around

With a Geiger counter in my hand / I’m a-goin’ out to stake me some government land

The song references Vernon Pick, known as the “Uranium King of America,” after making a lucky strike during nine months of prospecting in Utah. His rags-to-riches story represented exactly what all prospectors hope to achieve—Pick sold his Delta claim to Atlas Corporation in 1954 for $9 million (equivalent to nearly $100 million today), transforming from amateur prospector to mining mogul almost overnight. The tune may be catchy with twangy guitar and honky-tonk piano, but Pick’s uranium claim at Delta, Utah, still stands as a monument to atomic age dreams.

Both moments share that familiar gold rush optimism: the certainty that this next big thing will change everything, all upside and no shadow. The parallels are unsettling. In the 1950s, uranium prospectors scoured the Colorado Plateau for bright yellow carnotite stains against red sandstone, their Geiger counters confirming what their eyes could spot: veins of atomic potential hidden in plain sight. Today’s tech companies operate much the same way, waving transformer models across every problem space.

The uranium rush transformed prospecting from an individual pursuit into a government-backed industrial complex. Ordinary citizens dreamed that like Pick they could become overnight millionaires, while the Atomic Energy Commission promised nuclear power would revolutionize society. Tech giants make similar promises about AI, as capital floods into any company with a viable claim. During each rush, entrepreneurs made fortunes not just from the resource itself but from selling essential tools to prospectors—San Francisco merchants selling shovels during the gold rush, Utah suppliers providing Geiger counters during the uranium boom, and companies offering GPU clusters for today’s prospectors.

Where uranium revealed itself in shocking yellow crusts against desert rock, AI’s potential lies buried in the invisible patterns of data, waiting to be extracted and refined into something that could either illuminate or incinerate our world... and like those uranium prospectors, we might not know which until after we’ve unleashed its power. But uranium's cautionary tale isn’t just about get-rich-quick schemes. Its real lesson lies in how a powerful technology, improperly managed, can devastate communities and environments.

Nuclear testing scarred both the American West and the Pacific, leaving behind contaminated water tables and cancer clusters in Arizona, Nevada and Utah, while turning pristine Pacific atolls into badlands with radioactive coconut palms. What toxic legacy will AI’s unrestrained development leave in its wake? We’re already seeing the environmental cost of training large language models, with data centers consuming more electricity than some small nations. Equally concerning is the human cost—the content moderators exposed to digital toxicity, the artists watching their craft being mined for training data, and the knowledge workers whose expertise is being extracted and commodified to make them easier to replace.

The average professional understands AI about as well as the average American understood nuclear fission in the 1950s. Both inspired equal measures of terror and avarice in the public imagination. The difference? We learned to handle uranium with careful protocols and containment strategies. AI development, by contrast, remains a form of uranium fever with companies racing to refine this powerful resource before anyone can establish proper safety measures.

What will AI’s Three Mile Island moment be? Or will we create digital Chernobyls, catastrophic failures of automated systems that cascade beyond our ability to contain them? Perhaps we’re already experiencing a slower disaster, the meltdown of human agency and creativity in the face of industrial-scale cognitive extraction. The uranium rush ended when the costs became clear. The question isn’t whether AI’s hidden costs will surface, but whether we’ll recognize them before the damage becomes irreversible.

Sustainable Extraction?

Standing at the rim of Malakoff Diggins, you can’t help but feel the weight of choices made by people who couldn’t see the full consequences of their actions. Those hydraulic miners knew they were poisoning rivers with mercury, but the pressure to produce overwhelmed environmental concerns. They were men like my grandfather, trying to make a living in a system that valued extraction over sustainability.

Today’s tech leaders understand they’re burning out their workforce, but quarterly earnings expectations trump human costs. We’re caught in the same extractive logic that turned gold mining from an entrepreneurial pursuit into an industrial operation. People making software are not just tired because they are hammering away in the digital equivalent of mineshafts, they are exhausted because the value is being extracted from them. The wasteland of layoff posts on LinkedIn shows how companies grind then discard people, set aside like toxic mine tailings.

Where do we go from here? How do we reconcile the field we entered vs the industry we occupy now?

One choice is to put on our helmets and focus on the safety of those mining on the front lines. As a manager, can I ensure my crew meets quota without cave-ins or explosions? Or, do we leave that to the crew coming in behind us… They applied for a job, knowing this was a mine; a career, not a vocation. Privately held companies seem to fair better, maintaining the agency to think long-term and treat their employees as humans vs exploitable resources. Be thoughtful about the organizations you join and how your values align.

In today’s hypercompetitive market, suggesting we slow down and prioritize sustainability might seem naive. When your competitors ship features daily, and investors demand constant growth, taking your foot off the extraction accelerator feels like unilateral disarmament. The mining industry faced similar pressures: every company knew their practices were unsustainable, but none could afford to change alone.

Yet change did come through a combination of regulation, innovation, and shifting social values, even if you would not call it a green endeavor. The tech industry’s path to sustainability might look different, but the lesson remains: practices that seem economically necessary can change when their actual costs become apparent and alternatives emerge. Companies that develop sustainable practices early will have an advantage when that change comes.

The best people I know are trying to reform the system from within, pushing for sustainable practices and human-centered development, like the mining engineers who eventually developed environmental remediation techniques. But individual choices won’t solve systemic problems. The mining industry didn’t become sustainable because individual miners chose better practices: it required legislation, regulation, and a fundamental shift in how society valued environmental protection over pure profit. Silicon Valley’s human sustainability crisis demands similar structural changes.

The choice facing tech isn't whether to keep mining people... that seam is already showing signs of depletion. So many apps look like gradient-tinted copies of each other, a vast pile of mediocre sameness. Like an over-excavated shaft, we’re seeing structural failures: engineers burning out from unsustainable sprint cycles, designers losing their creative instincts to AI-generated shortcuts, and knowledge workers watching their expertise become training data for the very tools that might replace them.

The lack of ingenuity is not just impacting software, the focus on profits over potential is strip-mining our culture. Why does Hollywood keep making the same franchise over and over again? I am Marvel’ed out, are you? The video game industry already went off a cliff. A friend recently opined “Think about all of the creativity of the iPad games in 2012. Angry Birds! Temple Run, Plants vs Zombies, Zuma, and later award winning games like Monument Valley.”

Look in the App Store now and the top games are all derivative money machines. Game publishers and large studios in PC and console gaming were forerunners of quarrying creativity and decades of hire-ship-fire cycles have brought them to a desolate wasteland bereft of originality. Upcoming AAA titles are being downgraded to AA titles, the market is crumbling for a myriad reasons but a dearth of ingenuity is the top reason from my perspective.

What would sustainable cognitive harvesting look like? It may mean treating human creativity as a renewable resource rather than an exhaustible commodity. It may require new metrics that value long-term innovation over short-term productivity. It could also mean abandoning the extractive model entirely, finding ways to cultivate rather than mine human potential.

The neural bedrock we thought inexhaustible is starting to crack. The choice is whether we’ll learn from mining’s history or repeat its mistakes. Will we wait until our cognitive landscapes are as scarred as Malakoff Diggins before we change course? Or will we find a way to make tech sustainable, not just environmentally, but humanely?