Open Pit Programming: Silicon Valley’s Industrial Extraction of Human Potential Part I

Silicon Valley’s open pit mines aren’t visible on Google Earth. There are no scarred landscapes or towering tailings piles, just gleaming, half-empty corporate campuses where algorithms extract value with the same ruthless efficiency that hydraulic cannons once carved through California hillsides. The terrain here is mental rather than mineral, but the extraction methods are equally brutal. Productivity metrics and key performance indicators drill through cross-functional teams like diamond-tipped bits through granite.

In 1849 prospectors came to California with picks and pans, seeking gold in mountain streams. In 2025, they come with MacBooks and algorithms. The tools have changed; the fever hasn’t. I’ve witnessed this transformation from both sides of the extraction economy. Months before the 1848 strike at Sutter’s Mill my great-great-great grandfather rode into the town now known as Nevada City, California.

In the Empire Mine State Historic Park museum in Grass Valley, Nevada City’s twin mountain town on the other side of the Banner Mountain ridge, my grandfather’s face stares out from a sepia-toned photograph. A handsome, heavy-lidded bruiser in an iron lamp helmet, his expression holds the same wariness I now see in Zoom-weary eyes. My father bridged these worlds, leaving the family’s mining tradition to drive ninety minutes each way to Rancho Cordova’s tech corridor, managing engineers who built avionics and defense software instead of ore crushers.

My father’s photo sits on my desk. When I look at it during late-night Slack catchup sessions, I wonder what he would make of tech today. Would he recognize the same boom and bust patterns of craft giving way to industrial extraction?

I am liminal between Millennials and Gen X, identifying as a member of the Oregon Trail Generation, a fitting designation for a descendant of actual wagon train settlers. I have always straddled the divide between the California of yore and Silicon Valley’s world of tomorrow. The house I grew up in was heated by wood stoves, but full of computers, modems, and a graveyard of multi-colored wires. It still stands on the original 600-acre homestead’s scrappy remains, shrinking to a few acres over two centuries. My family’s journey from miners to corporate employees mirrors tech’s evolution. As my dad traded mining for a corporate paycheck via a career in the Air Force, developers have traded garage startups for FAANG jobs.

In today’s tech landscape, the resource being mined isn’t buried in quartz veins: it’s threaded through neural networks of developers, designers, program managers, and product managers. The industrialization of tech mirrors mining’s evolution with unsettling precision. Where individual prospectors once panned streams with practiced swirl, lone programmers crafted elegant code in green text on black screens.

As mining corporations consolidated claims and systematized extraction, tech giants absorbed startups and standardized development practices. The tools evolved, from pickaxe to hydraulic cannon from the command line to AI assistant, but the pattern remains: find a resource, extract it, scale the exploitation, and move on when depleted. We didn’t learn from the ravaged hillsides and poisoned waterways of the mining era; we simply shifted our extraction to a new frontier, mining minds instead of mountains.

Any metaphor breaks if you pull it too hard. Tech workers aren’t descending into literal mine shafts, and no one’s dying from continuous integration fumes. But metaphors help us see patterns we might otherwise miss. When I trace tech’s evolution from individual craft to industrial extraction, I’m not claiming identical experiences—I’m highlighting similar patterns of resource exploitation. These patterns reveal how industries mature, treat their workers, and impact their environments. The parallel isn’t perfect, but it illuminates our present moment in ways that might help us choose a better future.

Fool’s Gold and Failed IPOs

Like the miners who followed promising veins of ore from shaft to shaft, I now travel between tech hubs, watching San Francisco’s latest boom-and-bust cycle unfold. My friends shake their heads and say, “The city just isn’t what it used to be.” Rudyard Kipling’s 1890 observation that San Francisco was “a mad city, inhabited for the most part by perfectly insane people” captures a truth that persists today.

The first big boom was in 1849 when almost 300,000 prospectors arrived in California, turbocharging San Francisco’s economy overnight. The Barbary Coast neighborhood, just north of current-day Union Square, was a dimly lit warren of brothels, dance halls, gambling parlors, and saloons, all ready and willing to lighten the pockets of miners looking for a good time. The cycle lurched from boom to bust: crashing in 1857, then surging again with the Comstock silver strike in Nevada in 1859. It rolled through the 1906 earthquake's destruction and rebuilding, past the wartime boom of WWII, into the unhinged days of Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s, through the cocaine-fueled excess of the 1980s, and into the vapid decadence of the dot-com dawn.

As prospectors once traded physical gold for mining stock certificates, the Bay Area transformed raw minerals into market speculation. By the dawn of the 21st century, those paper stocks had become digital options, and keyboards replaced pickaxes. The dot-com bubble was a precipitous rise and rapid crash, with the NASDAQ plummeting nearly 80% from its peak on March 10, 2000, to its trough on October 9, 2002. Such a staggering collapse wiped away more than $4.6 trillion in market value in just over two years.

Honestly, that doesn’t feel far removed from looking at the stock market in 2025.

The vibe in SF today is more of a gritty lull. Walking through Union Square, you can see rows of shuttered stores; the most recent on the chopping block is the 6-story flagship Macy’s, following on the heels of the Westfield Nordstrom. The department stores cite a lack of sales and high crime as reasons for leaving the city. I won’t go down the rabbit hole of that specific debate, but walking along Montgomery St from my hotel to the FiDi, I scurry past more closed storefronts than any open for business.

Tech’s recent peak was more of a slow burn, building incrementally from the Great Recession through to 2022, then seeing explosive growth during the pandemic. The San Francisco Chronicle reports, “The share of San Francisco jobs in tech grew from 3.6% in 2006 to 18.7% in 2021… Looking at tech’s share of the private-sector payroll, the trajectory is even steeper: It went from 5.4% of payroll in 2006 to 32.8% in 2021.” No wonder the city has been transforming further during the current macroeconomic shift.

Today’s laid-off tech workers scroll LinkedIn with the same desperate hope that broke prospectors once scanned riverbanks, both searching for that next opportunity to sustain them. The digital marketplace has become our modern Barbary Coast, where the fortunate display their wealth while others hunt for any chance to recover their losses. Tone-blinded by privilege, tech bros post about only hiring A players or ham-handedly trying to flaunt their “insights” on using AI. Sadder posts are from the people who weathered one layoff from a tech giant only to be laid off again from their new rebound role, or heartbreakingly, those whose Cobra benefits are running out before their chemo regime finishes. Now joined by waves of DOGE-impacted government workers.

Optimism and over-hiring during the pandemic played a role in these rounds of layoffs, but something feels different from the other cycles of belt-tightening. One of my fellow tech workers commented that the new ways of working smack of McKinsey-style consulting optimizations: skewed design to product-to-engineer ratios, fewer managers with more direct reports, attempts to operationalize experience, and velocity prioritized over humane work practices. Or as I frame it: shareholder-centered value doesn’t give a fuck about well-being or burnout.

The deadpan faces of tech employees in post-reorg town hall Zoom meetings echo the miner’s flat expressions in those photos at the Empire Mine State Park Museum: guarded and lacking trust. Modern tech management resembles nothing so much as open pit mining: massive operations optimized for maximum extraction.

The physical toll of mining, the danger, the sheer bodily exhaustion, has no direct parallel in tech work. My grandfather’s generation faced hazards I’ll never know behind my standing desk and ergonomic chair. I understand that my compensation level is ridiculous compared to what he was paid. But knowledge work exacts its own costs.

Mental exhaustion may not show up in X-rays, but its physical toll manifests in emergency room visits for stress-induced heart problems, panic attacks mistaken for cardiac events, and bodies breaking down from sustained cortisol overload. The physical injuries may be less visible than a mining accident, but they ripple just as destructively through families and communities, driven by the same pressure to extract maximum value regardless of human cost.

Hazards faced by mine workers varied by privilege and power; who had to work the most dangerous shafts, who got the safest jobs, who could afford to take time off when injured. Today’s tech industry perpetuates similar hierarchies of harm. Women and people of color disproportionately bear the burden of these harsh working conditions, often assigned the most draining emotional labor while receiving less recognition and compensation.

The dismantling of DEI programs and support networks has only intensified this imbalance. When companies optimize for “efficiency,” it’s these same workers who are most likely to be stripped of accommodations, pushed beyond sustainable limits, and targeted in layoffs. Like the mining companies that relegated marginalized workers to the most hazardous tasks, tech’s culture of exhaustion doesn't extract equally from all veins.

The cruel irony? Taking medical leave to recover often brands you with performance ratings that make you vulnerable in the next round of layoffs, regardless of labor laws. And those who do get laid off can’t even pause to heal; the brutal process of job hunting demands immediate performance, forcing burned-out workers to jump straight from one crushing pressure to another.

Staking a Claim on .com

Men willing to leave civilization for literal buried treasure, my forbears included, were lawless and hungry for adventure. Theft, brutality, sexism, and racism were as plentiful as dusty miners rolling into town with small leather sacks of gold to spend. It was a rough life, fueled by bacon, beans, and sludgy cowboy coffee in chipped cobalt-blue enamel metal mugs, but every miner believed—gamblers to the end—that the next claim would be the mother lode.

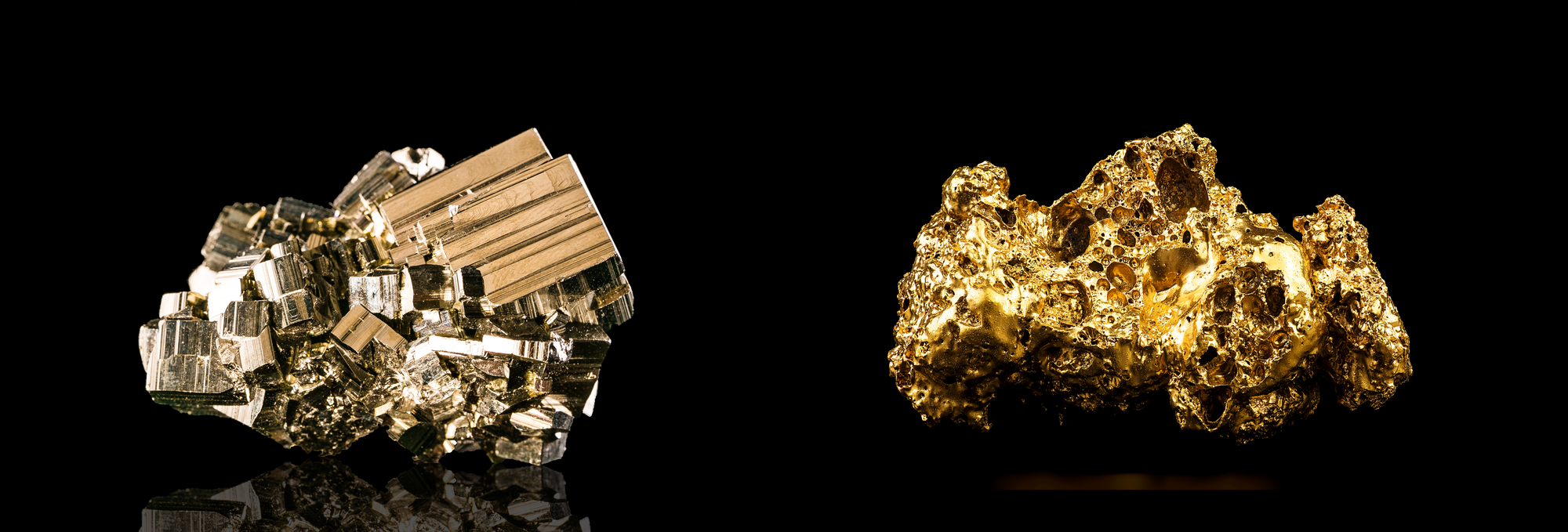

The dream of striking it rich never fully ended. Summer days on the Yuba River, my dad would bring his green metal pan, teaching us to swirl sand and water with that same patient rhythm his father taught him. We’d catch flashes of pyrite and feel that familiar surge of hope before recognizing fool’s gold, but even that disappointment carried echoes of every prospector’s eternal optimism. While we did it for family fun, others still hunt these same rivers with deadly serious intent. Gold fever hasn’t faded; it's just gone mainstream. Search IMDB and you'll find 47 prospecting shows and documentaries between 2006 and 2024, each feeding that same ancient dream that the next sweep of the pan might change everything.

In the early Gold Rush, anyone could hit pay dirt. Prospecting a placer claim was easy; just find enough gold in sand or gravel from alluvial runoff that a prudent man would find valuable. It could be using a pan if it was a one man operation. Or, to speed things up, a few more hands could build a series of sluices, diverting water from a sandy-bottomed river through a wooden channel to trap nuggets and flakes.

Strike gold? Hammer out 4 ft stakes to mark the boundary of the claim, like the startup version of buying the URL for the next hot idea. Then, get a shotgun and chase off claim jumpers trying to seize the land. The parallels to domain squatting feel apt until you dig deeper. Gold country wasn't empty land waiting to be claimed: it belonged to the Nisenan tribes living along the Yuba, American, and Bear rivers. My ancestors weren't just staking claims; they were part of a wave of Westerners systematically displacing indigenous people from their ancestral lands.

Early software pioneers yearned for a sense of adventure as much as those ’49ers did. David Byrne’s 1986 surreal musical satire True Stories keys into the trend of technical creation for the joy of it. Spaulding Gray’s role as civic leader Earl Culver is eerily prescient as he intones, “They’re working and inventing because they like it! Economics is become a spiritual thing.” We see Byrne’s narrator character running into aptly titled Computer Guy at the mall, picking up a stack of components to build his own PC at home. A visual echo of Culver’s statement, “There’s no concept of weekends anymore!”

Like those early days in the California foothills, when a prospector could still make a living with just a pan and patience, the early web felt full of possibility. Each new coding language mastered, each successful upload was like panning for pixels. For me something was intoxicating about the flow of building in BBEdit, uploading the images and HTML files via FTP using my US Robotics Sportster 14,400 Fax Modem, and then refreshing the URL to see my work live on “the net.” There was craft and magic in it then, before the industrialization of every codebase.

I am not pining for the “good old days” of cowboy coding, modern development practices exist for good reasons. But it’s fair to ask: have we over-corrected? Does every project need the full weight of an industrial-scale pipeline? We’ve built elaborate systems to extract maximum efficiency, complete with Jira tickets and CI/CD pipelines for even the simplest applications. Like mining companies that built massive hydraulic operations to extract ever-smaller amounts of gold, we’ve created increasingly complex infrastructure to chase diminishing returns. Perhaps we’re over-engineering the mechanics while under-thinking the human elements, optimizing for velocity while losing sight of pragmatism, building robust deployment pipelines while neglecting developer well-being.

Around 2013, I started freelancing at a small educational startup no one had heard of yet. I got a chance to design their pitch deck. That work helped secure $5 million in Series A funding, and I became a founding team member at what would become MasterClass. It was deeply satisfying to help build a platform that connects millions with the craft and wisdom of true masters; seeing the product grow from concept to cultural touchstone. But like so many mining claims, that satisfaction came at a steep price: my health, my sanity, and ultimately my marriage even if I was high-fived by Christina Aguilera at her class launch party as the only female engineer.

Today, I’m an expert at building software for people who make software. The thrill of shipping products is still there, but the effort has become heavier, the meaning of it all feels thinner. I’m one of the lucky ones, contributing at a company I trust and respect, but that seems increasingly rare in an industry that’s shifted from solving problems to syphoning value. I'm not just building tools anymore: I’m trying to keep the human element alive in an increasingly inhuman system.

I see software veterans posting about their new occupations: the former PM with a greeting cards business or the peer talking about the master gardener program they just joined for their sabbatical. In Zoom coffee chats the full-time employed look surreptitiously side to side, as if anyone is watching, before sharing their exit plan and how many months or years it will take. The joy of building software didn’t vanish in a single moment, it seeped away gradually, like heat from bathwater. You don’t notice the change until suddenly you’re shivering, wondering how long you’ve been sitting in the cold.

Part 2: Surface Mining, AI’s Atomic Moment & Sustainable Extraction